4D (4th Dimension) 3.5.1 serial key or number

4D (4th Dimension) 3.5.1 serial key or number

Spacetime

In physics, spacetime is any mathematical model which fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensionalmanifold. Spacetime diagrams can be used to visualize relativistic effects, such as why different observers perceive where and when events occur differently.

Until the 20th century, it was assumed that the 3-dimensional geometry of the universe (its spatial expression in terms of coordinates, distances, and directions) was independent of one-dimensional time. However, in , Albert Einstein based a work on special relativity on two postulates:

- The laws of physics are invariant (i.e., identical) in all inertial systems (i.e., non-accelerating frames of reference)

- The speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers, regardless of the motion of the light source.

The logical consequence of taking these postulates together is the inseparable joining together of the four dimensions—hitherto assumed as independent—of space and time. Many counterintuitive consequences emerge: in addition to being independent of the motion of the light source, the speed of light is constant regardless of the frame of reference in which it is measured; the distances and even temporal ordering of pairs of events change when measured in different inertial frames of reference (this is the relativity of simultaneity); and the linear additivity of velocities no longer holds true.

Einstein framed his theory in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies). His theory was an advance over Lorentz's theory of electromagnetic phenomena and Poincaré's electrodynamic theory. Although these theories included equations identical to those that Einstein introduced (i.e., the Lorentz transformation), they were essentially ad&#;hoc models proposed to explain the results of various experiments—including the famous Michelson–Morley interferometer experiment—that were extremely difficult to fit into existing paradigms.

In , Hermann Minkowski—once one of the math professors of a young Einstein in Zürich—presented a geometric interpretation of special relativity that fused time and the three spatial dimensions of space into a single four-dimensional continuum now known as Minkowski space. A key feature of this interpretation is the formal definition of the spacetime interval. Although measurements of distance and time between events differ for measurements made in different reference frames, the spacetime interval is independent of the inertial frame of reference in which they are recorded.[1]

Minkowski's geometric interpretation of relativity was to prove vital to Einstein's development of his general theory of relativity, wherein he showed how mass and energycurve flat spacetime into a pseudo-Riemannian manifold.

Introduction[edit]

Definitions[edit]

Non-relativistic classical mechanics treats time as a universal quantity of measurement which is uniform throughout space, and separate from space. Classical mechanics assumes that time has a constant rate of passage, independent of the observer's state of motion, or anything external.[2] Furthermore, it assumes that space is Euclidean; it assumes that space follows the geometry of common sense.[3]

In the context of special relativity, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space, because the observed rate at which time passes for an object depends on the object's velocity relative to the observer. General relativity also provides an explanation of how gravitational fields can slow the passage of time for an object as seen by an observer outside the field.

In ordinary space, a position is specified by three numbers, known as dimensions. In the Cartesian coordinate system, these are called x, y, and z. A position in spacetime is called an event, and requires four numbers to be specified: the three-dimensional location in space, plus the position in time (Fig.&#;1). Spacetime is thus four dimensional. An event is something that happens instantaneously at a single point in spacetime, represented by a set of coordinates x, y, z and t.

The word "event" used in relativity should not be confused with the use of the word "event" in normal conversation, where it might refer to an "event" as something such as a concert, sporting event, or a battle. These are not mathematical "events" in the way the word is used in relativity, because they have finite durations and extents. Unlike the analogies used to explain events, such as firecrackers or lightning bolts, mathematical events have zero duration and represent a single point in spacetime.

The path of a particle through spacetime can be considered to be a succession of events. The series of events can be linked together to form a line which represents a particle's progress through spacetime. That line is called the particle's world line.[4]

Mathematically, spacetime is a manifold, which is to say, it appears locally "flat" near each point in the same way that, at small enough scales, a globe appears flat.[5] An extremely large scale factor, (conventionally called the speed-of-light) relates distances measured in space with distances measured in time. The magnitude of this scale factor (nearly , kilometres or , miles in space being equivalent to one second in time), along with the fact that spacetime is a manifold, implies that at ordinary, non-relativistic speeds and at ordinary, human-scale distances, there is little that humans might observe which is noticeably different from what they might observe if the world were Euclidean. It was only with the advent of sensitive scientific measurements in the mids, such as the Fizeau experiment and the Michelson–Morley experiment, that puzzling discrepancies began to be noted between observation versus predictions based on the implicit assumption of Euclidean space.[6]

In special relativity, an observer will, in most cases, mean a frame of reference from which a set of objects or events is being measured. This usage differs significantly from the ordinary English meaning of the term. Reference frames are inherently nonlocal constructs, and according to this usage of the term, it does not make sense to speak of an observer as having a location. In Fig.&#;1&#;1, imagine that the frame under consideration is equipped with a dense lattice of clocks, synchronized within this reference frame, that extends indefinitely throughout the three dimensions of space. Any specific location within the lattice is not important. The latticework of clocks is used to determine the time and position of events taking place within the whole frame. The term observer refers to the entire ensemble of clocks associated with one inertial frame of reference.[7]–22 In this idealized case, every point in space has a clock associated with it, and thus the clocks register each event instantly, with no time delay between an event and its recording. A real observer, however, will see a delay between the emission of a signal and its detection due to the speed of light. To synchronize the clocks, in the data reduction following an experiment, the time when a signal is received will be corrected to reflect its actual time were it to have been recorded by an idealized lattice of clocks.

In many books on special relativity, especially older ones, the word "observer" is used in the more ordinary sense of the word. It is usually clear from context which meaning has been adopted.

Physicists distinguish between what one measures or observes (after one has factored out signal propagation delays), versus what one visually sees without such corrections. Failure to understand the difference between what one measures/observes versus what one sees is the source of much error among beginning students of relativity.[8]

History[edit]

By the mids, various experiments such as the observation of the Arago spot and differential measurements of the speed of light in air versus water were considered to have proven the wave nature of light as opposed to a corpuscular theory.[9] Propagation of waves was then assumed to require the existence of a waving medium; in the case of light waves, this was considered to be a hypothetical luminiferous aether.[note 1] However, the various attempts to establish the properties of this hypothetical medium yielded contradictory results. For example, the Fizeau experiment of demonstrated that the speed of light in flowing water was less than the sum of the speed of light in air plus the speed of the water by an amount dependent on the water's index of refraction. Among other issues, the dependence of the partial aether-dragging implied by this experiment on the index of refraction (which is dependent on wavelength) led to the unpalatable conclusion that aether simultaneously flows at different speeds for different colors of light.[10] The famous Michelson–Morley experiment of (Fig.&#;1&#;2) showed no differential influence of Earth's motions through the hypothetical aether on the speed of light, and the most likely explanation, complete aether dragging, was in conflict with the observation of stellar aberration.[6]

George Francis FitzGerald in , and Hendrik Lorentz in , independently proposed that material bodies traveling through the fixed aether were physically affected by their passage, contracting in the direction of motion by an amount that was exactly what was necessary to explain the negative results of the Michelson–Morley experiment. (No length changes occur in directions transverse to the direction of motion.)

By , Lorentz had expanded his theory such that he had arrived at equations formally identical with those that Einstein were to derive later (i.e. the Lorentz transform), but with a fundamentally different interpretation. As a theory of dynamics (the study of forces and torques and their effect on motion), his theory assumed actual physical deformations of the physical constituents of matter.[11]– Lorentz's equations predicted a quantity that he called local time, with which he could explain the aberration of light, the Fizeau experiment and other phenomena. However, Lorentz considered local time to be only an auxiliary mathematical tool, a trick as it were, to simplify the transformation from one system into another.

Other physicists and mathematicians at the turn of the century came close to arriving at what is currently known as spacetime. Einstein himself noted, that with so many people unraveling separate pieces of the puzzle, "the special theory of relativity, if we regard its development in retrospect, was ripe for discovery in "[12]

An important example is Henri Poincaré,[13][14]–80,93–95 who in argued that the simultaneity of two events is a matter of convention.[15][note 2] In , he recognized that Lorentz's "local time" is actually what is indicated by moving clocks by applying an explicitly operational definition of clock synchronization assuming constant light speed.[note 3] In and , he suggested the inherent undetectability of the aether by emphasizing the validity of what he called the principle of relativity, and in /[16] he mathematically perfected Lorentz's theory of electrons in order to bring it into accordance with the postulate of relativity. While discussing various hypotheses on Lorentz invariant gravitation, he introduced the innovative concept of a 4-dimensional spacetime by defining various four vectors, namely four-position, four-velocity, and four-force.[17][18] He did not pursue the 4-dimensional formalism in subsequent papers, however, stating that this line of research seemed to "entail great pain for limited profit", ultimately concluding "that three-dimensional language seems the best suited to the description of our world".[18] Furthermore, even as late as , Poincaré continued to believe in the dynamical interpretation of the Lorentz transform.[11]– For these and other reasons, most historians of science argue that Poincaré did not invent what is now called special relativity.[14][11]

In , Einstein introduced special relativity (even though without using the techniques of the spacetime formalism) in its modern understanding as a theory of space and time.[14][11] While his results are mathematically equivalent to those of Lorentz and Poincaré, Einstein showed that the Lorentz transformations are not the result of interactions between matter and aether, but rather concern the nature of space and time itself. He obtained all of his results by recognizing that the entire theory can be built upon two postulates: The principle of relativity and the principle of the constancy of light speed.

Einstein performed his analysis in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies without reference to forces) rather than dynamics. His work introducing the subject was filled with vivid imagery involving the exchange of light signals between clocks in motion, careful measurements of the lengths of moving rods, and other such examples.[19][note 4]

In addition, Einstein in superseded previous attempts of an electromagnetic mass–energy relation by introducing the general equivalence of mass and energy, which was instrumental for his subsequent formulation of the equivalence principle in , which declares the equivalence of inertial and gravitational mass. By using the mass–energy equivalence, Einstein showed, in addition, that the gravitational mass of a body is proportional to its energy content, which was one of early results in developing general relativity. While it would appear that he did not at first think geometrically about spacetime,[21] in the further development of general relativity Einstein fully incorporated the spacetime formalism.

When Einstein published in , another of his competitors, his former mathematics professor Hermann Minkowski, had also arrived at most of the basic elements of special relativity. Max Born recounted a meeting he had made with Minkowski, seeking to be Minkowski's student/collaborator:[22]

I went to Cologne, met Minkowski and heard his celebrated lecture 'Space and Time' delivered on 2 September […] He told me later that it came to him as a great shock when Einstein published his paper in which the equivalence of the different local times of observers moving relative to each other was pronounced; for he had reached the same conclusions independently but did not publish them because he wished first to work out the mathematical structure in all its splendor. He never made a priority claim and always gave Einstein his full share in the great discovery.

Minkowski had been concerned with the state of electrodynamics after Michelson's disruptive experiments at least since the summer of , when Minkowski and David Hilbert led an advanced seminar attended by notable physicists of the time to study the papers of Lorentz, Poincaré et al. However, it is not at all clear when Minkowski began to formulate the geometric formulation of special relativity that was to bear his name, or to which extent he was influenced by Poincaré's four-dimensional interpretation of the Lorentz transformation. Nor is it clear if he ever fully appreciated Einstein's critical contribution to the understanding of the Lorentz transformations, thinking of Einstein's work as being an extension of Lorentz's work.[23]

On 5 November (a little more than a year before his death), Minkowski introduced his geometric interpretation of spacetime in a lecture to the Göttingen Mathematical society with the title, The Relativity Principle (Das Relativitätsprinzip).[note 5] On 21 September , Minkowski presented his famous talk, Space and Time (Raum und Zeit),[24] to the German Society of Scientists and Physicians. The opening words of Space and Time include Minkowski's famous statement that "Henceforth, space for itself, and time for itself shall completely reduce to a mere shadow, and only some sort of union of the two shall preserve independence." Space and Time included the first public presentation of spacetime diagrams (Fig.&#;1&#;4), and included a remarkable demonstration that the concept of the invariant interval (discussed below), along with the empirical observation that the speed of light is finite, allows derivation of the entirety of special relativity.[note 6]

The spacetime concept and the Lorentz group are closely connected to certain types of sphere, hyperbolic, or conformal geometries and their transformation groups already developed in the 19th century, in which invariant intervals analogous to the spacetime interval are used.[note 7]

Einstein, for his part, was initially dismissive of Minkowski's geometric interpretation of special relativity, regarding it as überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit (superfluous learnedness). However, in order to complete his search for general relativity that started in , the geometric interpretation of relativity proved to be vital, and in , Einstein fully acknowledged his indebtedness to Minkowski, whose interpretation greatly facilitated the transition to general relativity.[11]– Since there are other types of spacetime, such as the curved spacetime of general relativity, the spacetime of special relativity is today known as Minkowski spacetime.

Spacetime in special relativity[edit]

Spacetime interval[edit]

In three dimensions, the distance between two points can be defined using the Pythagorean theorem:

Although two viewers may measure the x, y, and z position of the two points using different coordinate systems, the distance between the points will be the same for both (assuming that they are measuring using the same units). The distance is "invariant".

In special relativity, however, the distance between two points is no longer the same if measured by two different observers when one of the observers is moving, because of Lorentz contraction. The situation is even more complicated if the two points are separated in time as well as in space. For example, if one observer sees two events occur at the same place, but at different times, a person moving with respect to the first observer will see the two events occurring at different places, because (from their point of view) they are stationary, and the position of the event is receding or approaching. Thus, a different measure must be used to measure the effective "distance" between two events.

In four-dimensional spacetime, the analog to distance is the interval. Although time comes in as a fourth dimension, it is treated differently than the spatial dimensions. Minkowski space hence differs in important respects from four-dimensional Euclidean space. The fundamental reason for merging space and time into spacetime is that space and time are separately not invariant, which is to say that, under the proper conditions, different observers will disagree on the length of time between two events (because of time dilation) or the distance between the two events (because of length contraction). But special relativity provides a new invariant, called the spacetime interval, which combines distances in space and in time. All observers who measure time and distance carefully will find the same spacetime interval between any two events. Suppose an observer measures two events as being separated in time by and a spatial distance

Then the spacetime interval

between the two events that are separated by a distance

in space and by

in the

-coordinate is:

or for three space dimensions,

[28]

The constant the speed of light, converts time units (like seconds) into space units (like meters). Seconds times meters/second = meters.

Although for brevity, one frequently sees interval expressions expressed without deltas, including in most of the following discussion, it should be understood that in general, means

, etc. We are always concerned with differences of spatial or temporal coordinate values belonging to two events, and since there is no preferred origin, single coordinate values have no essential meaning.

The equation above is similar to the Pythagorean theorem, except with a minus sign between the and the

terms. The spacetime interval is the quantity

not

itself. The reason is that unlike distances in Euclidean geometry, intervals in Minkowski spacetime can be negative. Rather than deal with square roots of negative numbers, physicists customarily regard

as a distinct symbol in itself, rather than the square of something.[21]

Because of the minus sign, the spacetime interval between two distinct events can be zero. If is positive, the spacetime interval is timelike, meaning that two events are separated by more time than space. If

is negative, the spacetime interval is spacelike, meaning that two events are separated by more space than time. Spacetime intervals are zero when

In other words, the spacetime interval between two events on the world line of something moving at the speed of light is zero. Such an interval is termed lightlike or null. A photon arriving in our eye from a distant star will not have aged, despite having (from our perspective) spent years in its passage.

A spacetime diagram is typically drawn with only a single space and a single time coordinate. Fig.&#;2&#;1 presents a spacetime diagram illustrating the world lines (i.e. paths in spacetime) of two photons, A and B, originating from the same event and going in opposite directions. In addition, C illustrates the world line of a slower-than-light-speed object. The vertical time coordinate is scaled by so that it has the same units (meters) as the horizontal space coordinate. Since photons travel at the speed of light, their world lines have a slope of ±1. In other words, every meter that a photon travels to the left or right requires approximately nanoseconds of time.

There are two sign conventions in use in the relativity literature:

and

These sign conventions are associated with the metric signatures(+&#;−&#;−&#;−) and (−&#;+&#;+&#;+). A minor variation is to place the time coordinate last rather than first. Both conventions are widely used within the field of study.

Reference frames[edit]

To gain insight in how spacetime coordinates measured by observers in different reference frames compare with each other, it is useful to work with a simplified setup with frames in a standard configuration. With care, this allows simplification of the math with no loss of generality in the conclusions that are reached. In Fig.&#;2&#;2, two Galilean reference frames (i.e. conventional 3-space frames) are displayed in relative motion. Frame S belongs to a first observer O, and frame S′ (pronounced "S&#;prime") belongs to a second observer O′.

- The x, y, z axes of frame S are oriented parallel to the respective primed axes of frame S′.

- Frame S′ moves in the x-direction of frame S with a constant velocity v as measured in frame S.

- The origins of frames S and S′ are coincident when time t = 0 for frame S and t′ = 0 for frame S′.[4]

Fig.&#;2&#;3a redraws Fig.&#;2&#;2 in a different orientation. Fig.&#;2&#;3b illustrates a spacetime diagram from the viewpoint of observer O. Since S and S′ are in standard configuration, their origins coincide at times t&#;=&#;0 in frame S and t′&#;=&#;0 in frame S′. The ct′ axis passes through the events in frame S′ which have x′&#;=&#;0. But the points with x′&#;=&#;0 are moving in the x-direction of frame S with velocity v, so that they are not coincident with the ct axis at any time other than zero. Therefore, the ct′ axis is tilted with respect to the ct axis by an angle θ given by

The x′ axis is also tilted with respect to the x axis. To determine the angle of this tilt, we recall that the slope of the world line of a light pulse is always&#;±1. Fig.&#;2&#;3c presents a spacetime diagram from the viewpoint of observer O′. Event P represents the emission of a light pulse at x′&#;=&#;0, ct′&#;=&#;−a. The pulse is reflected from a mirror situated a distance a from the light source (event Q), and returns to the light source at x′&#;=&#;0,&#;ct′&#;=&#;a (event R).

The same events P, Q, R are plotted in Fig.&#;2&#;3b in the frame of observer O. The light paths have slopes&#;=&#;1 and&#;−1, so that △PQR forms a right triangle with PQ and QR both at 45 degrees to the x and ct axes. Since OP&#;=&#;OQ&#;=&#;OR, the angle between x′ and x must also be θ.[4]–

While the rest frame has space and time axes that meet at right angles, the moving frame is drawn with axes that meet at an acute angle. The frames are actually equivalent. The asymmetry is due to unavoidable distortions in how spacetime coordinates can map onto a Cartesian plane, and should be considered no stranger than the manner in which, on a Mercator projection of the Earth, the relative sizes of land masses near the poles (Greenland and Antarctica) are highly exaggerated relative to land masses near the Equator.

Light cone[edit]

In Fig. , event&#;O is at the origin of a spacetime diagram, and the two diagonal lines represent all events that have zero spacetime interval with respect to the origin event. These two lines form what is called the light cone of the event&#;O, since adding a second spatial dimension (Fig.&#;2&#;5) makes the appearance that of two right circular cones meeting with their apices at&#;O. One cone extends into the future (t>0), the other into the past (t<0).

A light (double) cone divides spacetime into separate regions with respect to its apex. The interior of the future light cone consists of all events that are separated from the apex by more time (temporal distance) than necessary to cross their spatial distance at lightspeed; these events comprise the timelike future of the event&#;O. Likewise, the timelike past comprises the interior events of the past light cone. So in timelike intervals &#;ct is greater than &#;x, making timelike intervals positive. The region exterior to the light cone consists of events that are separated from the event&#;O by more space than can be crossed at lightspeed in the given time. These events comprise the so-called spacelike region of the event&#;O, denoted "Elsewhere" in Fig.&#;2&#;4. Events on the light cone itself are said to be lightlike (or null separated) from&#;O. Because of the invariance of the spacetime interval, all observers will assign the same light cone to any given event, and thus will agree on this division of spacetime.[21]

The light cone has an essential role within the concept of causality. It is possible for a not-faster-than-light-speed signal to travel from the position and time of&#;O to the position and time of D (Fig.&#;2&#;4). It is hence possible for event&#;O to have a causal influence on event&#;D. The future light cone contains all the events that could be causally influenced by O. Likewise, it is possible for a not-faster-than-light-speed signal to travel from the position and time of A, to the position and time of O. The past light cone contains all the events that could have a causal influence on O. In contrast, assuming that signals cannot travel faster than the speed of light, any event, like e.g.&#;B or&#;C, in the spacelike region (Elsewhere), cannot either affect event&#;O, nor can they be affected by event&#;O employing such signalling. Under this assumption any causal relationship between event&#;O and any events in the spacelike region of a light cone is excluded.[29]

Relativity of simultaneity[edit]

All observers will agree that for any given event, an event within the given event's future light cone occurs after the given event. Likewise, for any given event, an event within the given event's past light cone occurs before the given event. The before–after relationship observed for timelike-separated events remains unchanged no matter what the reference frame of the observer, i.e. no matter how the observer may be moving. The situation is quite different for spacelike-separated events. Fig.&#;2&#;4

Tous Comptes Faits Mac Serial Info

Explore this option by following the steps mentioned below. pulliOpen your PCMac and launch iTunes on it. liliConnect your iPhone to PCMac by using USB lightning cable and wait till iTunes detects your iPhone. liliClick on your device and then from the options on the left side of the window, choose ldquo;Summaryrdquo.

.What’s New in the 4D (4th Dimension) 3.5.1 serial key or number?

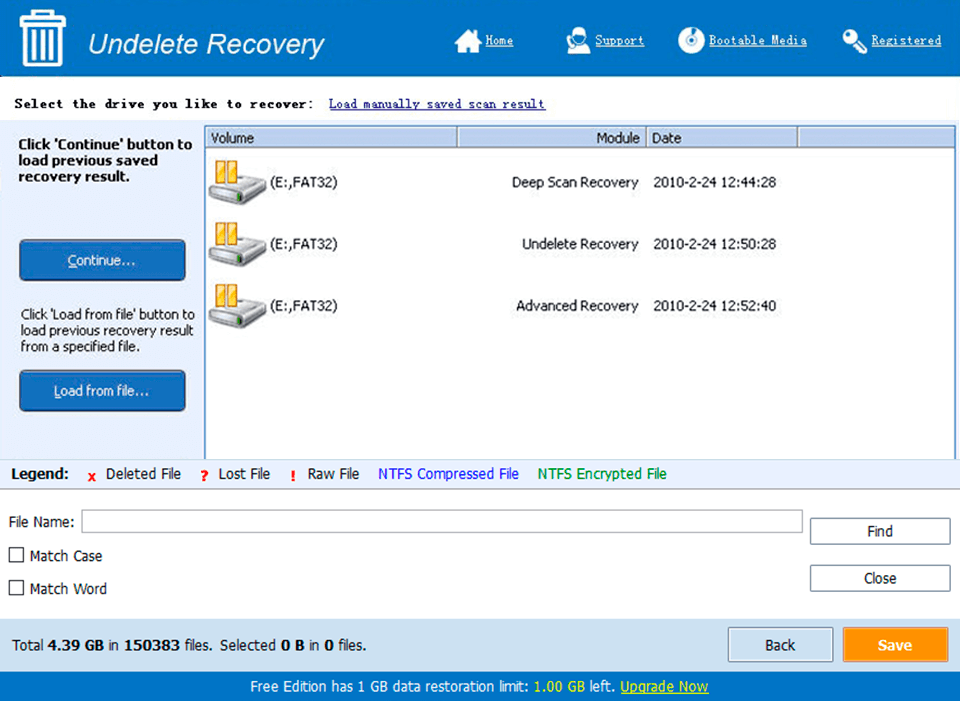

Screen Shot

System Requirements for 4D (4th Dimension) 3.5.1 serial key or number

- First, download the 4D (4th Dimension) 3.5.1 serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: