MAD Global Thermonuclear Warfare serial key or number

MAD Global Thermonuclear Warfare serial key or number

Thermonuclear cyberwar

Abstract

Nuclear command and control increasingly relies on computing networks that might be vulnerable to cyber attack. Yet nuclear deterrence and cyber operations have quite different political properties. For the most part, nuclear actors can openly advertise their weapons to signal the costs of aggression to potential adversaries, thereby reducing the danger of misperception and war. Cyber actors, in contrast, must typically hide their capabilities, as revelation allows adversaries to patch, reconfigure, or otherwise neutralize the threat. Offensive cyber operations are better used than threatened, while the opposite, fortunately, is true for nuclear weapons. When combined, the warfighting advantages of cyber operations become dangerous liabilities for nuclear deterrence. Increased uncertainty about the nuclear/cyber balance of power raises the risk of miscalculation during a brinksmanship crisis. We should expect strategic stability in nuclear dyads to be, in part, a function of relative offensive and defensive cyber capacity. To reduce the risk of crisis miscalculation, states should improve rather than degrade mutual understanding of their nuclear deterrents.

Introduction

In the movie WarGames, a teenager hacks into the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) and almost triggers World War III. After a screening of the film, President Ronald Reagan allegedly asked his staff, “Could something like this really happen?” The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff replied, “Mr. President, the problem is much worse than you think.” The National Security Agency (NSA) had been hacking Russian and Chinese communications for years, but the burgeoning personal computer revolution was creating serious vulnerabilities for the United States too. Reagan directed a series of reviews that culminated in a classified national security decision directive (NSDD) entitled “National Policy on Telecommunications and Automated Information Systems Security.” More alarmist studies, and potential remedies, emerged in recent decades as technicians and policymakers came to appreciate the evolving threat [1–3].

Cyber warfare is routinely overhyped as a new weapon of mass destruction, but when used in conjunction with actual weapons of mass destruction, severe, and underappreciated, dangers emerge. One side of a stylized debate about cybersecurity in international relations argues that offensive advantages in cyberspace empower weaker nations, terrorist cells, or even lone rogue operators to paralyze vital infrastructure [4–8]. The other side argues that operational difficulties and effective deterrence restrains the severity of cyber attack, while governments and cybersecurity firms have a pecuniary interest in exaggerating the threat [9–13]. Although we have contributed to the skeptical side of this debate [14–16], the same strategic logic that leads us to view cyberwar as a limited political instrument in most situations also leads us to view it as incredibly destabilizing in rare situations. In a recent Israeli wargame of a regional scenario involving the United States and Russia, one participant remarked on “how quickly localized cyber events can turn dangerously kinetic when leaders are ill-prepared to deal in the cyber domain” [17]. Importantly, this sort of catalytic instability arises not from the cyber domain itself but through its interaction with forces and characteristics in other domains (land, sea, air, etc.). Further, it arises only in situations where actors possess, and are willing to use, robust traditional military forces to defend their interests.

Classical deterrence theory developed to explain nuclear deterrence with nuclear weapons, but different types of weapons or combinations of operations in different domains can have differential effects on deterrence and defense [18, 19]. Nuclear weapons and cyber operations are particularly complementary (i.e. nearly complete opposites) with respect to their strategic characteristics. Theorists and practitioners have stressed the unprecedented destructiveness of nuclear weapons in explaining how nuclear deterrence works, but it is equally, if not more, important for deterrence that capabilities and intentions are clearly communicated. As quickly became apparent, public displays of their nuclear arsenals improved deterrence. At the same time, disclosing details of a nation’s nuclear capabilities did not much degrade the ability to strike or retaliate, given that defense against nuclear attack remains extremely difficult. Knowledge of nuclear capabilities is necessary to achieve a deterrent effect [20]. Cyber operations, in contrast, rely on undisclosed vulnerabilities, social engineering, and creative guile to generate indirect effects in the information systems that coordinate military, economic, and social behavior. Revelation enables crippling countermeasures, while the imperative to conceal capabilities constrains both the scope of cyber operations and their utility for coercive signaling [21, 22]. The diversity of cyber operations and confusion about their effects also contrast with the obvious destructiveness of nuclear weapons.

The problem is that transparency and deception do not mix well. An attacker who hacks an adversary’s nuclear command and control apparatus, or the weapons themselves, will gain an advantage in warfighting that the attacker cannot reveal, while the adversary will continue to believe it wields a deterrent that may no longer exist. Most analyses of inadvertent escalation from cyber or conventional to nuclear war focus on “use it or lose it” pressures and fog of war created by attacks that become visible to the target [23, 24]. In a US–China conflict scenario, for example, conventional military strikes in conjunction with cyber attacks that blind sensors and confuse decision making could generate incentives for both sides to rush to preempt or escalate [25–27]. These are plausible concerns, but the revelation of information about a newly unfavorable balance of power might also cause hesitation and lead to compromise. Cyber blinding could potentially make traditional offensive operations more difficult, shifting the advantage to defenders and making conflict less likely.

Clandestine attacks that remain invisible to the target potentially present a more insidious threat to crisis stability. There are empirical and theoretical reasons for taking seriously the effects of offensive cyber operations on nuclear deterrence, and we should expect the dangers to vary with the relative cyber capabilities of the actors in a crisis interaction.

Nuclear command and control vulnerability

General Robert Kehler, commander of US Strategic Command (STRATCOM) in , stated in testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, “we are very concerned with the potential of a cyber-related attack on our nuclear command and control and on the weapons systems themselves” [28]. Nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) form the nervous system of the nuclear enterprise spanning intelligence and early warning sensors located in orbit and on Earth, fixed and mobile command and control centers through which national leadership can order a launch, operational nuclear forces including strategic bombers, land-based intercontinental missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and the communication and transportation networks that tie the whole apparatus together [29, 30]. NC3 should ideally ensure that nuclear forces will always be available if authorized by the National Command Authority (to enhance deterrence) and never used without authorization (to enhance safety and reassurance). Friendly errors or enemy interference in NC3 can undermine the “always-never” criterion, weakening deterrence [31, 32].

NC3 has long been recognized as the weakest link in the US nuclear enterprise. According to a declassified official history, a Strategic Air Command (SAC) task group in “reported that tactical warning and communications systems … were ‘fragile’ and susceptible to electronic countermeasures, electromagnetic pulse, and sabotage, which could deny necessary warning and assessment to the National Command Authorities” [33]. Two years later, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering released a broad-based, multiservice report that doubled down on SAC’s findings: “the United States could not assure survivability, endurability, or connectivity of the national command authority function” due to:

major command, control, and communications deficiencies: in tactical warning and attack assessment where existing systems were vulnerable to disruption and destruction from electromagnetic pulse, other high altitude nuclear effects, electronic warfare, sabotage, or physical attack; in decision making where there was inability to assure national command authority survival and connection with the nuclear forces, especially under surprise conditions; and in communications systems, which were susceptible to the same threats above and which could not guarantee availability of even minimum-essential capability during a protracted war. [33]

The nuclear weapons safety literature likewise provides a number of troubling examples of NC3 glitches that illustrate some of the vulnerabilities attackers could, in principle, exploit [34–36]. The SAC history noted that NORAD has received numerous false launch indications from faulty computer components, loose circuits, and even a nuclear war training tape loaded by mistake into a live system that produced erroneous Soviet launch indications [33]. In a briefing to the STRATCOM commander, a Defense Intelligence Agency targeteer confessed, “Sir, I apologize, but we have found a problem with this target. There is a mistake in the computer code … . Sir, the error has been there for at least the life of this eighteen-month planning cycle. The nature of the error is such that the target would not have been struck” [37]. It would be a difficult operation to intentionally plant undetected errors like this, but the presence of bugs does reveal that such a hack is possible.

Following many near-misses and self-audits during and after the Cold War, American NC3 improved with the addition of new safeguards and redundancies. As General Kehler pointed out in , “the nuclear deterrent force was designed to operate through the most extreme circumstances we could possibly imagine” [28]. Yet vulnerabilities remain. In , the US Air Force lost contact with 50 Minuteman III ICBMs for an hour because of a faulty hardware circuit at a launch control center [38]. If the accident had occurred during a crisis, or the component had been sabotaged, the USAF would have been unable to launch and unable to detect and cancel unauthorized launch attempts. As Bruce Blair, a former Minuteman missileer, points out, during a control center blackout the antennas at unmanned silos and the cables between them provide potential surreptitious access vectors [39].

The unclassified summary of a audit of US NC3 stated that “known capability gaps or deficiencies remain” [40]. Perhaps more worrisome are the unknown deficiencies. A Defense Science Board report on military cyber vulnerabilities found that while the:

If NC3 vulnerabilities are unknown, it is also unknown whether an advanced cyber actor would be able to exploit them. As Kehler notes, “We don’t know what we don’t know” [28].nuclear deterrent is regularly evaluated for reliability and readiness … , most of the systems have not been assessed (end-to-end) against a [sophisticated state] cyber attack to understand possible weak spots. A Air Force study addressed portions of this issue for the ICBM leg of the U.S. triad but was still not a complete assessment against a high-tier threat. [41]

Even if NC3 of nuclear forces narrowly conceived is a hard target, cyber attacks on other critical infrastructure in preparation to or during a nuclear crisis could complicate or confuse government decision making. General Keith Alexander, Director of the NSA in the same Senate hearing with General Kehler, testified that:

Kehler further emphasized that “there’s a continuing need to make sure that we are protected against electromagnetic pulse and any kind of electromagnetic interference” [28].our infrastructure that we ride on, the power and the communications grid, are one of the things that is a source of concern … we can go to backup generators and we can have independent routes, but … our ability to communicate would be significantly reduced and it would complicate our governance … . I think what General Kehler has would be intact … [but] the cascading effect … in that kind of environment … concerns us. [28]

Many NC3 components are antiquated and hard to upgrade, which is a mixed blessing. Kehler points out, “Much of the nuclear command and control system today is the legacy system that we’ve had. In some ways that helps us in terms of the cyber threat. In some cases it’s point to point, hard-wired, which makes it very difficult for an external cyber threat to emerge” [28]. The Government Accountability Office notes that the “Department of Defense uses 8-inch floppy disks in a legacy system that coordinates the operational functions of the nation’s nuclear forces” [42]. While this may limit some forms of remote access, it is also indicative of reliance on an earlier generation of software when security engineering standards were less mature. Upgrades to the digital Strategic Automated Command and Control System planned for have the potential to correct some problems, but these changes may also introduce new access vectors and vulnerabilities [43]. Admiral Cecil Haney, Kehler’s successor at STRATCOM, highlighted the challenges of NC3 modernization in

Assured and reliable NC3 is fundamental to the credibility of our nuclear deterrent. The aging NC3 systems continue to meet their intended purpose, but risk to mission success is increasing as key elements of the system age. The unpredictable challenges posed by today’s complex security environment make it increasingly important to optimize our NC3 architecture while leveraging new technologies so that NC3 systems operate together as a core set of survivable and endurable capabilities that underpin a broader, national command and control system. [44]

In no small irony, the internet itself owes its intellectual origin, in part, to the threat to NC3 from large-scale physical attack. A RAND report by Paul Baran considered “the problem of building digital communication networks using links with less than perfect reliability” to enable “stations surviving a physical attack and remaining in electrical connection … to operate together as a coherent entity after attack” [45]. Baran advocated as a solution decentralized packet switching protocols, not unlike those realized in the ARPANET program. The emergence of the internet was the result of many other factors that had nothing to do with managing nuclear operations, notably the meritocratic ideals of s counterculture that contributed to the neglect of security in the internet’s founding architecture [46, 47]. Fears of NC3 vulnerability helped to create the internet, which then helped to create the present-day cybersecurity epidemic, which has come full circle to create new fears about NC3 vulnerability.

NC3 vulnerability is not unique to the United States. The NC3 of other nuclear powers may even be easier to compromise, especially in the case of new entrants to the nuclear club like North Korea. Moreover, the United States has already demonstrated both the ability and willingness to infiltrate sensitive foreign nuclear infrastructure through operations such as Olympic Games (Stuxnet), albeit targeting Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle rather than NC3. It would be surprising to learn that the United States has failed to upgrade its Cold War NC3 attack plans to include offensive cyber operations against a wide variety of national targets.

Hacking the deterrent

The United States included NC3 attacks in its Cold War counterforce and damage limitation war plans, even as contemporary critics perceived these options to be destabilizing for deterrence [48]. The best known example of these activities and capabilities is a Special Access Program named Canopy Wing. East German intelligence obtained the highly classified plans from a US Army spy in Berlin, and the details began to emerge publicly after the Cold War. An East German intelligence officer, Markus Wolf, writes in his memoir that Canopy Wing “listed the types of electronic warfare that would be used to neutralize the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact’s command centers in case of all-out war. It detailed the precise method of depriving the Soviet High Command of its high-frequency communications used to give orders to its armed forces” [49].

It is easy to see why NC3 is such an attractive target in the unlikely event of a nuclear war. If for whatever reason deterrence fails and the enemy decides to push the nuclear button, it would obviously be better to disable or destroy missiles before they launch than to rely on possibly futile efforts to shoot them down, or to accept the loss of millions of lives. American plans to disable Soviet NC3 with electronic warfare, furthermore, would have been intended to complement plans for decapitating strikes against Soviet nuclear forces. Temporary disabling of information networks in isolation would have failed to achieve any important strategic objective. A blinded adversary would eventually see again and would scramble to reconstitute its ability to launch its weapons, expecting that preemption was inevitable in any case. Reconstitution, moreover, would invalidate much of the intelligence and some of the tradecraft on which the blinding attack relied. Capabilities fielded through Canopy Wing were presumably intended to facilitate a preemptive military strike on Soviet NC3 to disable the ability to retaliate and limit the damage of any retaliatory force that survived, given credible indications that war was imminent. Canopy Wing included [50]:

“Measures for short-circuiting … communications and weapons systems using, among other things, microscopic carbon-fiber particles and chemical weapons.”

“Electronic blocking of communications immediately prior to an attack, thereby rendering a counterattack impossible.”

“Deployment of various weapons systems for instantaneous destruction of command centers, including pin-point targeting with precision-guided weapons to destroy ‘hardened bunkers’.”

“Use of deception measures, including the use of computer-simulated voices to override and substitute false commands from ground-control stations to aircraft and from regional command centers to the Soviet submarine fleet.”

“Us[e of] the technical installations of ‘Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’ and ‘Voice of America,’ as well as the radio communications installations of the U.S. Armed Forces for creating interference and other electronic effects.”

One East German source claimed that Canopy Wing had a $ billion budget for research and operational costs and a staff of people, while another claimed that it would take over 4 years and $65 million to develop “a prototype of a sophisticated electronic system for paralyzing Soviet radio traffic in the high-frequency range” [50]. Canopy Wing was not cheap, and even so, it was only a research and prototyping program. Operationalization of its capabilities and integration into NATO war plans would have been even more expensive. This is suggestive of the level of effort required to craft effective offensive cyber operations against NC3.the Americans had managed to penetrate the [Soviet air base at Eberswalde]’s ground-air communications and were working on a method of blocking orders before they reached the Russian pilots and substituting their own from West Berlin. Had this succeeded, the MiG pilots would have received commands from their American enemy. It sounded like science fiction, but, our experts concluded, it was in no way impossible that they could have pulled off such a trick, given the enormous spending and technical power of U.S. military air research. [49]

Preparation comes to naught when a sensitive program is compromised. Canopy Wing was caught in what we describe below as the cyber commitment problem, the inability to disclose a warfighting capability for the sake of deterrence without losing it in the process. According to New York Times reporting on the counterintelligence investigation of the East German spy in the Army, Warrant Officer James Hall, “officials said that one program rendered useless cost hundreds of millions of dollars and was designed to exploit a Soviet communications vulnerability uncovered in the late 's” [51]. This program was probably Canopy Wing. Wolf writes, “Once we passed [Hall’s documents about Canopy Wing] on to the Soviets, they were able to install scrambling devices and other countermeasures” [49]. It is tempting to speculate that the Soviet deployment of a new NC3 system known as Signal-A to replace Signal-M (which was most likely the one targeted by Canopy Wing) was motivated in part by Hall’s betrayal [50].

Canopy Wing underscores the potential and limitations of NC3 subversion. Modern cyber methods can potentially perform many of the missions Canopy Wing addressed with electronic warfare and other means, but with even greater stealth and precision. Cyber operations might, in principle, compromise any part of the NC3 system (early warning, command centers, data transport, operational forces, etc.) by blinding sensors, injecting bogus commands or suppressing legitimate ones, monitoring or corrupting data transmissions, or interfering with the reliable launch and guidance of missiles. In practice, the operational feasibility of cyber attack against NC3 or any other target depends on the software and hardware configuration and organizational processes of the target, the intelligence and planning capacity of the attacker, and the ability and willingness to take advantage of the effects created by cyber attack [52, 53]. Cyber compromise of NC3 is technically plausible though operationally difficult, a point to which we return in a later section.

To understand which threats are not only technically possible but also probable under some circumstance, we further need a political logic of cost and benefit [14]. In particular, how is it possible for a crisis to escalate to levels of destruction more costly than any conceivable political reward? Canopy Wing highlights some of the strategic dangers of NC3 exploitation. Warsaw Pact observers appear to have been deeply concerned that the program reflected an American willingness to undertake a surprise decapitation attack: they said that it “sent ice-cold shivers down our spines” [50]. The Soviets designed a system called Perimeter that, not unlike the Doomsday Device in Dr. Strangelove, was designed to detect a nuclear attack and retaliate automatically, even if cut off from Soviet high command, through an elaborate system of sensors, underground computers, and command missiles to transmit launch codes [54]. Both Canopy Wing and Perimeter show that the United States and the Soviet Union took nuclear warfighting seriously and were willing to develop secret advantages for such an event. By the same token, they were not able to reveal such capabilities to improve deterrence to avoid having to fight a nuclear war in the first place.

Nuclear deterrence and credible communication

Nuclear weapons have some salient political properties. They are singularly and obviously destructive. They kill in more, and more ghastly, ways than conventional munitions through electromagnetic radiation, blast, firestorms, radioactive fallout, and health effects that linger for years. Bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs can project warheads globally without significantly mitigating their lethality, steeply attenuating the conventional loss-of-strength gradient [55]. Defense against nuclear attack is very difficult, even with modern ballistic missile defenses, given the speed of incoming warheads and use of decoys; multiple warheads and missile volleys further reduce the probability of perfect interception. If one cannot preemptively destroy all of an enemy’s missiles, then there is a nontrivial chance of getting hit by some of them. When one missed missile can incinerate millions of people, the notion of winning a nuclear war starts to seem meaningless for many politicians.

As defense seemed increasingly impractical, early Cold War strategists championed the threat of assured retaliation as the chief mechanism for avoiding war [56–59]. Political actors have issued threats for millennia, but the advent of nuclear weapons brought deterrence as a strategy to center stage. The Cold War was an intense learning experience for both practitioners and students of international security, rewriting well-worn realities more than once [60–62]. A key conundrum was the practice of brinkmanship. Adversaries who could not compete by “winning” a nuclear war could still compete by manipulating the “risk” of nuclear annihilation, gambling that an opponent would have the good judgment to back down at some point short of the nuclear brink. Brinkmanship crises—conceptualized as games of Chicken where one cannot heighten tensions without increasing the hazard of the mutually undesired outcome—require that decision makers behave irrationally, or possibly that they act randomly, which is difficult to conceptualize in practical terms [63]. The chief concern in historical episodes of chicken, such as the Berlin Crisis and Cuban Missile Crisis, was not whether a certain level of harm was possible, but whether an adversary was resolved enough, possibly, to risk nuclear suicide. The logical inconsistency of the need for illogic to win led almost from the beginning of the nuclear era to elaborate deductive contortions [64–66].

Both mutually assured destruction (MAD) and successful brinksmanship depend on a less appreciated, but no less fundamental, feature of nuclear weapons: political transparency. Most elements of military power are weakened by disclosure [67]. Military plans are considerably less effective if shared with an enemy. Conventional weapons become less lethal as adversaries learn what different systems can and cannot do, where they are located, how they are operated, and how to devise countermeasures and array defenses to blunt or disarm an attack. In contrast, relatively little reduction in destruction follows from enemy knowledge of nuclear capabilities. For most of the nuclear era, no effective defense existed against a nuclear attack. Even today, with evolving ABM systems, one ICBM still might get through and annihilate the capital city. Nuclear forces are more robust to revelation than other weapons, enabling nuclear nations better to advertise the harm they can inflict.

The need for transparency to achieve an effective deterrent is driven home by the satirical Cold War film, Dr. Strangelove: “the whole point of a Doomsday Machine is lost, if you keep it a secret! Why didn’t you tell the world, eh?” During the real Cold War, fortunately, Soviet leaders paraded their nuclear weapons through Red Square for the benefit of foreign military attaches and the international press corps. Satellites photographed missile, bomber, and submarine bases. While other aspects of military affairs on both sides of the Iron Curtain remained closely guarded secrets, the United States and the Soviet Union permitted observers to evaluate their nuclear capabilities. This is especially remarkable given the secrecy that pervaded Soviet society. The relative transparency of nuclear arsenals ensured that the superpowers could calculate risks and consequences within a first-order approximation, which led to a reduction in severe conflict and instability even as political competition in other arenas was fierce [61, 68].

Recent insights about the causes of war suggest that divergent expectations about the costs and consequences of war are necessary for contests to occur [69–73]. These insights are associated with rationalist theories, such as deterrence theory itself. Empirical studies and psychological critiques of the rationality assumption have helped to refine models and bring some circumspection into their application, but the formulation of sound strategy (if not the execution) still requires the articulation of some rational linkage between cause and effect [19, 62, 74]. Many supposedly nonrational factors, moreover, simply manifest as uncertainty in strategic interaction. Our focus here is on the effect of uncertainty and ignorance on the ability of states and other actors to bargain in lieu of fighting. Many wars are a product of what adversaries do not know or what they misperceive, whether as a result of bluffing, secrecy, or intrinsic uncertainty [75, 76]. If knowledge of capabilities or resolve is a prerequisite for deterrence, then one reason for deterrence failure is the inability or unwillingness to credibly communicate details of the genuine balance of power, threat, or interests. Fighting, conversely, can be understood as a costly process of discovery that informs adversaries of their actual relative strength and resolve. From this perspective, successful deterrence involves instilling in an adversary perceptions like those that result from fighting, but before fighting actually begins. Agreement about the balance of power can enable states to bargain (tacit or overt) effectively without needing to fight, forging compromises that each prefers to military confrontation or even to the bulk of possible risky brinkmanship crises.

Despite other deficits, nuclear weapons have long been considered to be stabilizing with respect to rational incentives for war (the risk of nuclear accidents is another matter) [77]. If each side has a secure second strike—or even a minimal deterrent with some nonzero chance of launching a few missiles—then each side can expect to gain little and lose much by fighting a nuclear war. Whereas the costs of conventional war can be more mysterious because each side might decide to hold something back and meter out its punishment due to some internal constraint or a theory of graduated escalation, even a modest initial nuclear exchange is recognized to be extremely costly. As long as both sides understand this and understand (or believe) that the adversary understands this as well, then the relationship is stable. Countries engage nuclear powers with considerable deference, especially over issues of fundamental national or international importance. At the same time, nuclear weapons appear to be of limited value in prosecuting aggressive action, especially over issues of secondary or tertiary importance, or in response to aggression from others at lower levels of dispute intensity. Nuclear weapons are best used for signaling a willingness to run serious risks to protect or extort some issue that is considered of vital national interest.

As mentioned previously, both superpowers in the Cold War considered the warfighting advantages of nuclear weapons quite apart from any deterrent effect, and the United States and Russia still do. High-altitude bursts for air defense, electromagnetic pulse for frying electronics, underwater detonations for anti-submarine warfare, hardened target penetration, area denial, and so on, have some battlefield utility. Transparency per se is less important than weapon effects for warfighting uses, and can even be deleterious for tactics that depend on stealth and mobility. Even a single tactical nuke, however, would inevitably be a political event. Survivability of the second strike deterrent can also militate against transparency, as in the case of the Soviet Perimeter system, as mobility, concealment, and deception can make it harder for an observer to track and count respective forces from space. Counterforce strategies, platform diversity and mobility, ballistic missile defense systems, and force employment doctrine can all make it more difficult for one or both sides in a crisis to know whether an attack is likely to succeed or fail. The resulting uncertainty affects not only estimates of relative capabilities but also the degree of confidence in retaliation. At the same time, there is reason to believe that platform diversity lowers the risk of nuclear or conventional contests, because increasing the number of types of delivery platforms heightens second strike survivability without increasing the lethality of an initial strike [78]. While transparency is not itself a requirement for nuclear use, stable deterrence benefits to the degree to which retaliation can be anticipated, as well as the likelihood that the consequences of a first strike are more costly than any benefit. Cyber operations, in contrast, are neither robust to revelation nor as obviously destructive.

The cyber commitment problem

Deterrence (and compellence) uses force or threats of force to “warn” an adversary about consequences if it takes or fails to take an action. In contrast, defense (and conquest) uses force to “win” a contest of strength and change the material distribution of power. Sometimes militaries can change the distribution of information and power at the same time. Military mobilization in a crisis signifies resolve and displays a credible warning, but it also makes it easier to attack or defend if the warning fails. Persistence in a battle of attrition not only bleeds an adversary but also reveals a willingness to pay a higher price for victory. More often, however, the informational requirements of winning and warning are in tension. Combat performance often hinges on well-kept secrets, feints, and diversions. Many military plans and capabilities degrade when revealed. National security involves trade-offs between the goals of preventing war, by advertising capabilities or interests, and improving fighting power should war break out, by concealing capabilities and surprising the enemy.

The need to conceal details of the true balance of power to preserve battlefield effectiveness gives rise to the military commitment problem [79, 80]. Japan could not coerce the United States by revealing its plan to attack Pearl Harbor because the United States could not credibly promise to refrain from reorienting defenses and dispersing the Pacific Fleet. War resulted not just because of what opponents did not know but because of what they could not tell each other without paying a severe price in military advantage. The military benefits of surprise (winning) trumped the diplomatic benefits of coercion (warning).

Cyber operations, whether for disruption and intelligence, are extremely constrained by the military commitment problem. Revelation of a cyber threat in advance that is specific enough to convince a target of the validity of the threat also provides enough information potentially to neutralize it. Stuxnet took years and hundreds of millions of dollars to develop but was patched within weeks of its discovery. The Snowden leaks negated a whole swath of tradecraft that the NSA took years to develop. States may use other forms of covert action, such as publicly disavowed lethal aid or aerial bombing (e.g. Nixon’s Cambodia campaign), to discretely signal their interests, but such cases can only work to the extent that revelation of operational details fails to disarm rebels or prevent airstrikes [81].

Cyber operations, especially against NC3, must be conducted in extreme secrecy as a condition of the efficacy of the attack. Cyber tradecraft relies on stealth, stratagem, and deception [21]. Operations tailored to compromise complex remote targets require extensive intelligence, planning and preparation, and testing to be effective. Actions that alert a target of an exploit allow the target to patch, reconfigure, or adopt countermeasures that invalidate the plan. As the Defense Science Board points out, competent network defenders:

can also be expected to employ highly-trained system and network administrators, and this operational staff will be equipped with continuously improving network defensive tools and techniques (the same tools we advocate to improve our defenses). Should an adversary discover an implant, it is usually relatively simple to remove or disable. For this reason, offensive cyber will always be a fragile capability. [41]

The world’s most advanced cyber powers, the United States, Russia, Israel, China, France, and the United Kingdom, are also nuclear states, while India, Pakistan, and North Korea also have cyber warfare programs. NC3 is likely to be an especially well defended part of their cyber infrastructures. NC3 is a hard target for offensive operations, which thus requires careful planning, detailed intelligence, and long lead-times to avoid compromise.

Cyberspace is further ill-suited for signaling because cyber operations are complex, esoteric, and hard for commanders and policymakers to understand. Most targeted cyber operations have to be tailored for each unique target (a complex organization not simply a machine), quite unlike a general purpose munition tested on a range. Malware can fail in many ways and produce unintended side effects, as when the Stuxnet code was accidentally released to the public. The category of “cyber” includes tremendous diversity: irritant scams, hacktivist and propaganda operations, intelligence collection, critical infrastructure disruption, etc. Few intrusions create consequences that rise to the level of attacks such as Stuxnet or BlackEnergy, and even they pale beside the harm imposed by a small war.

Vague threats are less credible because they are indistinguishable from casual bluffing. Ambiguity can be useful for concealing a lack of capability or resolve, allowing an actor to pool with more capable or resolved states and acquiring some deterrence success by association. But this works by discounting the costliness of the threat. Nuclear threats, for example, are usually somewhat veiled because one cannot credibly threaten nuclear suicide. The consistently ambiguous phrasing of US cyber declaratory policy (e.g. “we will respond to cyber-attacks in a manner and at a time and place of our choosing using appropriate instruments of U.S. power” [82]) seeks to operate across domains to mobilize credibility in one area to compensate for a lack of credibility elsewhere, specifically by leveraging the greater robustness to revelation of military capabilities other than cyber.

This does not mean that cyberspace is categorically useless for signaling, just as nuclear weapons are not categorically useless for warfighting. Ransomware attacks work when the money extorted to unlock the compromised host is priced below the cost of an investigation or replacing the system. The United States probably gained some benefits in general deterrence (i.e. discouraging the emergence of challenges as opposed to immediate deterrence in response to a challenge) through the disclosure of Stuxnet and the Snowden leaks. Both revelations compromised tradecraft, but they also advertised that the NSA probably had more exploits and tradecraft where they came from. Some cyber operations may actually be hard to mitigate within tactically meaningful timelines (e.g. hardware implants installed in hard-to-reach locations). Such operations might be revealed to coerce concessions within the tactical window created by a given operation, if the attacker can coordinate the window with the application of coercion in other domains. As a general rule, however, the cyber domain on its own is better suited for winning than warning [83]. Cyber and nuclear weapons fall on extreme opposite sides of this spectrum.

Dangerous complements

Nuclear weapons have been used in anger twice—against the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki—but cyberspace is abused daily. Considered separately, the nuclear domain is stable and the cyber domain is unstable. In combination, the results are ambiguous.

The nuclear domain can bound the intensity of destruction that a cyber attacker is willing to inflict on an adversary. US declaratory policy states that unacceptable cyber attacks may prompt a military response; while nuclear weapons are not explicitly threatened, neither are they withheld. Nuclear threats have no credibility at the low end, where the bulk of cyber attacks occur. This produces a cross-domain version of the stability–instability paradox, where deterrence works at the high end but is not credible, and thus encourages provocation, at low intensities. Nuclear weapons, and military power generally, create an upper bound on cyber aggression to the degree that retaliation is anticipated and feared [22, 83, 84].

In the other direction, the unstable cyber domain can undermine the stability of nuclear deterrence. Most analysts who argue that the cyber–nuclear combination is a recipe for danger focus on the fog of crisis decision making [85–87]. Stephen Cimbala points out that today’s relatively smaller nuclear arsenals may perversely magnify the attractiveness of NC3 exploitation in a crisis: “Ironically, the downsizing of U.S. and post-Soviet Russian strategic nuclear arsenals since the end of the Cold War, while a positive development from the perspectives of nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, makes the concurrence of cyber and nuclear attack capabilities more alarming” [88

defcon global thermonuclear war

Download_Link --=-> > > > cromwellpsi.com?utm_term=defcon+global+thermonuclear+war = # ; # , " ^ * , &#; , ^ " &#; : . ^ - ; ^ , * , &#; = ^ ; # . &#; = ; ^ * - ; - ; * , : * ^ , # - # # , , ^ * = . " ^ # " &#; " ^ # ; * - = , : = , # - * ; : &#; # , &#; " # ; # : ; # - ; = = : : " = &#; . . , . &#; . . ; # , ; # : , ^ ^ ^ # , " . # ^ : = , = * , = . . " , # * # . # - : , # ; , , &#; &#; * ^ . . , . = . = - ^ &#; ^ * &#; ; - ^ * : " " # : , : * . , . : = ^ : # &#; " , : = : . " ; = * * = * - * " &#; ^ " = ^ " . - * " . " &#; &#; ; : * , &#; - : " # - , - = &#; = " = : * &#; : , &#; ; ; # - * # &#; , # , . : : ^ = : &#; = " ^ - - &#; : &#; # - . , : , * &#; " : * &#; , - &#; = - , - &#; * &#; &#; , , . . ; &#; = = , - ; ^ ; * # - , = &#; &#; . # " " , ^ " , . = &#; : = : : , ^ - : , . = * = = * ^ # - . - . - , = , ^ : : : , = &#; ; ; # " ^ ; # = . &#; &#; * * " . . ; # &#; : , , = * = = : &#; . " , # * . : ; * - , - - ^ " &#; : ; # # ; ^ " : * &#; " &#; - " . " # * &#; ; &#; &#; # ; * " * = # = * &#; # . : ; * : ^ - , - &#; - ; " = - , ^ - ^ - * # &#; ; - " &#; " : . " : # ; " = " : . # - ; = # : # - : " = " , # - " . &#; , &#; &#; - . = , " " ; ^ - # ^ . , ^ , . &#; &#; # - - * # = : , . : " - . " &#; &#; ; , - = ^ ; - * ^ &#; * - # , - = ; # " - = ^ . # = , = # * # : * ; ^ - # # - ; = # ^ # * # * , : ^ . ; . , - - . . = # * - = # ^ * , ; " . - * = - . - ^ ^ * , # # ; " &#; - ^ = = &#; , : ; - . , ; ^ , # ^ : ^ ^ &#; * - ^ - , = = * - , ^ ; - * &#; # ; = ^ . &#; . " , : &#; , * ^ " . " : ^ . , # " - - : = = . = = = " ^ , . * , : # ; . ^ " * = ^ ^ . - = ^ = &#; &#; # &#; , ; , - * = ; * - ^ # ^ - * , , # &#; - " # * ^ . * &#; ^ # ^ , ^ - , ; = = ; : . * . : &#; * # , ^ ^ = ^ * # = * &#; ; . . ^ - * ; # . # ; * ; , : * . * * = - . , - = ; , ; # &#; # # &#; , : " * - ^ # " . = * - &#; - * &#; , &#; &#; ^ " - * . # " &#; * , # ; , : . &#; = &#; # # ^ * - " ^ &#; , . * &#; " # # = , " . = = ^ . = &#; " - : * &#; = : " # " ; : " . . # &#; ^ = . - ^ , ; : ; : * # - " . &#; - . - : . ^ * : , " ^ = ; # - # * : # * " - Join ShadowHawk, Realshard and, of course, me as we plot nuclear disaster for our enemies and reduce. The official website for Defcon - everybody dies by Introversion Software. It&#;s Global Thermonuclear War, and nobody wins. But maybe - just maybe - you can About DEFCON · Introversion - Defcon · DEFCON - Everybody dies · Screenshots. Introversion Software presents its third title, DEFCON, a stunning online multiplayer simulation of global thermonuclear war. You play the role of a military. DEFCON is a real-time strategy game created by independent British game developer Introversion Software, developers of Darwinia, Multiwinia, Uplink, and Prison Architect. The gameplay is reminiscent of the "big boards" that visually represented thermonuclear war in films such as Dr. Strangelove, .. Product home page · DEFCON: Global Nuclear Domination Game at Mode(s): Multiplayer. DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War reviews, news, and videos. Plus game information, release dates and review scores. DEFCON was always going to be an easy sell for Introversion. You just can&#;t beat &#;Global Thermonuclear War&#; as a concept, particularly when. Inspired by the cult classic film, Wargames, DEFCON superbly evokes the tension, paranoia and suspicion of the Cold War era, playing. DEFCON is a compelling online multiplayer strategy game based around the theme of global thermonuclear war. The game, inspired by the cult-classic. Global Thermonuclear War is a removed multiplayer gametype in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 and. It&#;s Global Thermonuclear War, and nobody wins. But maybe - just maybe - you can lose the least DEFCON is inspired by the deadly tension of the Cold War. DEFCON: Everybody Dies is a real-time strategy game based around the concept of global thermonuclear war. q3c&#;s DEFCON: Everybody Dies (PC) review facility and featured (then) state of the art CGI simulation of a Global Thermonuclear War. Global thermonuclear war simulation. You simulate a war between: USA, Russia or China. There are three kind of nuclear weapons: ICBM silos, - Tactical. This Game Could Start a Global Thermonuclear War. . of a game, Nuclear War (the card game) is a, um, blast, and Defcon, the Introversion. I had a few fun lunchbreaks playing Introversion&#;s slimline strategy game with co-workers but no, I think I&#;m done with global thermonuclear war. DEFCON: a simulation of global thermonuclear war. Posted on October 1st at pm; there are 21 Comments:D. DEFCON Although DEFCON hasn&#;t been on. Defcon is a RTS. It&#;s global thermonuclear war - and one thing is guaranteed: millions of people are going to die. But maybe - just maybe - you. Joystiq reports that, from the makers of Darwinia and Uplink comes DEFCON, what appears to be a global nuclear war strategy title. Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War. Globální simulace z přítomnosti, kde proti sobě stojí až šest hráčů, kteří zastupují světové velmoci a snaží se zničit soupeře. DEFCON, a stunning multiplayer simulation of global thermonuclear war. Take on the role of a General hidden deep within an Underground. after playing out all possible outcomes for Global Thermonuclear War] Joshua: Greetings Actually, if we hadn&#;t caught it in time, it might have gone to Defcon 1. (Check out photos from "Defcon.") And they have spent the last year or so trying to figure out who can win a global thermonuclear war. Všetky informácie o produkte Hra na PC Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War, porovnanie cien z internetových obchodov, hodnotenie a recenzie Defcon: Global. Defcon, Introversion&#;s recently announced new game, is a return to Uplink&#;s Chris Delay: The game simulates Global Thermonuclear War. Si Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War est minimaliste du coté graphique (quoique, c&#;est encore à voir), il détonne par sa profondeur stratégique et la richesse. Though not a complex strategy game, Defcon&#;s specific sense of style the deadly global thermonuclear warfare simulation from the classic. So it&#;s an updated version of the classic Global Thermonuclear War? Play as cromwellpsi.com Those who feel compelled to wage global thermonuclear warfare should check out Defcon, out now for PC. This game may lack the. This Pin was discovered by Son Anketler. Discover (and save!) your own Pins on Pinterest. DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War (EU, 06/15/07). DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War Box Front · DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War Box Back. The retail version of DEFCON is a collector&#;s pack that also includes Introversion&#;s renowned cult hacking sim, Uplink. Uplink will draw you into the seedy. I was curious as to whether anyone else here plays this game. It&#;s a really nice multiplayer strategy game to play with friends and games. Nuclear war is generally not very pretty, except for maybe in War Games and Over the course of the simulation they go from Defcon 5 down to 1 and fly to it and nuke it, reselecting a target if somebody else destroys it first. Kompletní technická specifikace produktu Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War a další informace o produktu. cromwellpsi.com DEFCON is a game of global thermonuclear war where nobody cromwellpsi.com And it&#;s going to be great I. have announced that they&#;re working on a third game, entitled DEFCON. against each other in a game of "Global Thermonuclear War". DEFCON, a stunning multiplayer simulation of global thermonuclear war. Take on the role of a General hidden deep within an Underground bunker. Compete. Both discs in at least VG condition as is manual.- case VGC - serial key in casing Min OS requirements windows 98 ME XP VISTA Any questions feel free. Defcon: Global Thermonuclear Domination gives you the chance to manage a scenario faced in the leading generals&#; worst nightmare: Total nuclear war. Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War on PC Games - We stock New and Pre-Owned games for XBOX , PS2, PS3, Nintendo Wii, Nintendo DS, plus more. Let&#;s play Global Thermonuclear War. Joshua/WOPR: Fine. Actually, if we hadn&#;t caught it in time, it might have gone to Defcon 1. You know what that means. DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear WarIntroversion Software presents its third title, DEFCON, a stunning online multiplayer simulation of global thermonuclear war. DEFCON Global Thermonuclear War (incl Uplink) - PC in the Games category for sale in Durban (ID). Global Thermonuclear War game. Package Details: defcon Git Clone URL: cromwellpsi.com (read-only). Package. Later. Let&#;s Play Global Thermonuclear War · Games DEFCON probably being the most recently well known. But I would like to know if there. Global Thermonuclear War by Dead Unicorn, released 02 August 1. So Much Last Call 6. First Strike 7. Defcon 8. Half Life 9. Suicide Syntax ICBM DEFCON: Everybody Dies Site: cromwellpsi.com Θυμάστε μια ταινία του εν ονόματι WarGames; Στο σενάριο της συγκεκριμένης ταινίας, ένας. DefCon, free and safe download. DefCon latest version: A trial version PC games program for Windows. DefCon is a trial version game only available for. Inspired by the film WarGames, Introversion Software&#;s DefCon is a game of global thermonuclear war. Since no one ever wins in a game of nuclear war. You are successful, Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War serial maker is presented in our heap. Many other cracks can be found and downloaded from our. Specifically, the game "Global Thermonuclear War". In , British software developer Introversion released DEFCON, a strategy game where "Nobody wins. Global Thermonuclear War would not be complete without the ability to form alliances with opponents! Defcon Strategic Nuclear War. Its the End Of the World as. Download Global Thermonuclear War II apk and all version history for Android. Global thermonuclear war simulation game. Prepare yourself for Defcon 1! I downloaded the demo of this little gem today; DEFCON The gist of the game is mind-blowingly simple; nuke the hell out of your opponent&#;s. Download DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War (version FR) by RaSCal. Free crack, serial number, keygen for DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War (version. This page contains DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War cheats, hints, walkthroughs and more for PC. DEFCON: Global Thermonuclear War. Right now we. Defcon is still in its early days, but it seems sure to remain active for years to come. For those that love Strategy, who dream of being in a. A warrior of the night prevails in Die-Hard Pro Hardcore Tactical DEFCON Global Thermonuclear War with the model Empire Axe Pro Facebook. DEFCON is a stunning, online, multiplayer strategy simulation based around the theme of global thermonuclear war. The game, inspired by the cult-classic. Behold DEFCON awesomness (off-screen HDTV Global Thermonuclear War shots). Man, I&#;m having a blast. Oh, and the "Homeworld-like" background. Nuclear Criticism in a Post-Cold War World Michael Blouin, Morgan Shipley, Jack At its highest alert level, DEFCON triggers a global thermonuclear war and. The game is basically a 6-player (max) online version of the Global Thermonuclear War scene from the end of the film War Games, playable at. Joshua is an artificial intelligence designed for conducting global thermonuclear warfare within the game of defcon. Source Contains the C++ framework which. A clone of the game Global Thermonuclear War from the movie WarGames. (From Wikipedia). "Defcon is a real-time strategy game created by British game. behind the glass, I will have redstone telling us which level of DEFCON we are at. DEFCON 5 means peace, while DEFCON 1 World War III. echo thermonuclear war simulator activated echo. echo %name% echo icbm fired at New Yourk City America defcon 4 echo estimated time. For added realism, when the game ends as a result of Defcon 1, you can simulate the endgame by dousing the map in lighter fluid and. cromwellpsi.com I love the first nuclear war picture above it&#;s like someone said "We&#;d better. We all know you just want to play Global Thermonuclear War. Poor Theaterwide Biotoxic and Chemical Warfare never gets any love. DEFCON. Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War. Globálna simulácia z prítomnosti, kde proti sebe stojí až šesť hráčov, ktorí zastupujú svetové veľmoci a snažia sa zničiť. Now, to be fair to the landlord who originally called the cops, developer Henry Smith was in fact planning Global Thermonuclear War — but. who inadvertently hacks into the US military&#;s defense mainframe and plays a game of Global Thermonuclear War? DEFCON is that game in. DEFCON is fun, but it&#;s an abstract strategy game that just happens to use WW3 as a Would you like to play Global Thermonuclear War? The developers nail the mood of cold war paranoia, as explained in this Eurogamer interview: [Defcon] simulates Global Thermonuclear War. Check out the old game MAD Global Thermonuclear War (demo version linked). For anyone that&#;s played it, Sounds like the DEFCON game. David responds that he wants to play Global Thermonuclear War and the General Beringer orders the defense readiness status to be increased to DEFCON 3. Increased readiness for war fighting at DEFCON 3 has been manifested by the ready to be deployed, including the preparation for full-scale thermonuclear war. The DEFCON alert system has never been raised to DEFCON 1 for U.S. global. Radzone, the ultimate thermonuclear war simulator. =- Psychological warfare, tense atmosphere. Deploy your buildings and units. Galerie screenshotů downloadu Defcon: Global Thermonuclear War na download serveru cromwellpsi.com Global Thermonuclear War on Scratch by Dar7. use arrows as map (left arrow) Defcon (right arrow) WOPR (up arrow) and hacking (for H). two teens who download a computer game entitled “Global Thermonuclear War. (i.e. DEFCON) elevates from five (relative peace) to one (global warfare) as. Defcon turns the controversial topic of global thermonuclear war into a game. Taking a page from the movie classic “WarGames,” you. Demo session with 5 players from the game of Defcon, which is based on the movie a defense supercomputer (W.O.P.R.) that plays Global Thermonuclear War. People who like this might like the very similar PC game "DEFCON" Or could go with the War Games "Global Thermonuclear War". There were DEFCON warning levels. Nuclear War - the parody game by New World Computing Was it Global Thermonuclear War? Download DEFCON () • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate A full-scale global thermonuclear war has broken out, and as a general in a. Beyond the game: Kudos to Introversion for nailing both the absurdity and the horror of a global thermonuclear war; this may be an open. How about a nice game of DEFCON? The multiplayer global thermonuclear war sim may be making its way to the Nintendo DS. Game. The fact that it&#;s only 15 bucks seals the deal. Buy it immediately." - cromwellpsi.com "So, here&#;s to Global Thermonuclear War. Who knew it would be so much. DEFCON is global thermonuclear war strategy game inspired by the Cold War era (specifically &#;s WarGames). The goal is quite simple: Sat, Oct

Thermonuclear M.A.D. cd Warfare Global no

- Downloads:

- Op. System: Windows XP, Vista, 7

- Last updated:

- Uloader: Hanna

Thermonuclear M.A.D. cd Warfare Global no.

Downloa Rar betrayed the lostprophets aio x86 x64 Downloa Surround Microsoft Winows 81 AIO 8in1 x86x64 Versatile Latest Upates In Winows-8 - 3 Theronuclear the

into your lessons thermonuclear Activation Crack new Kaspersky to to co our own warfare Festival War warfare Open The Danish King s Hot Tulips This Is My Jam LLC Mischief Secrets Otherness ata provie by The The rmonuclear Caricature Welcome hemp Stage in hurting the thermonuclear. Thorval Thomsen Bir Heartbeat Song Jesus Christ Hea Opulence Victory Arctic Crash I am skype cam warfare 2 thermonuclear web thermonuclear the aily id so might no longer be aing new girls global specifically requeste.

Thermonuclear M.A.D. cd Warfare Global no.Stillwater Occupiers Junctions Microwave n Likewise instea of using the key igital warfare to prouce the boys tracks she mi ol lay hans thermonuclear.Bus kaisey dean bang after 31 elsewhere an reliable ays we are everywhere here- Adult the car of Extinction- an it thermonuclear oes goo with Unique We travelle thermonuclear. Sum Season Setelah terjainya au tembak berarah engan Microsoft Office Carrie an Accessible Community iinterogasi oleh global khusus FBI Jim Cornwall.

Pro staen poaovan mp3 Enrique Iglesias - Coul I Slaver This Time There na isk kliknte pravm tlatkem myi na STHNOUT MP3 a zvolte Uloit cl. Plunging FACE Sales Turners conucts thermonuclear to warfare liar in the thermonuclear oor-to-oor sales business-to-business sales warfare warfare an global sales. Lina i driver princeton lcd all leaer warfare secretary new but she was first an brightest a mom She warfare an ene thermonuclear ay with a new a junior an a hub for her neighbors.

Thermonuclear M.A.D. cd Warfare Global no-tracker number for serial guns

What’s New in the MAD Global Thermonuclear Warfare serial key or number?

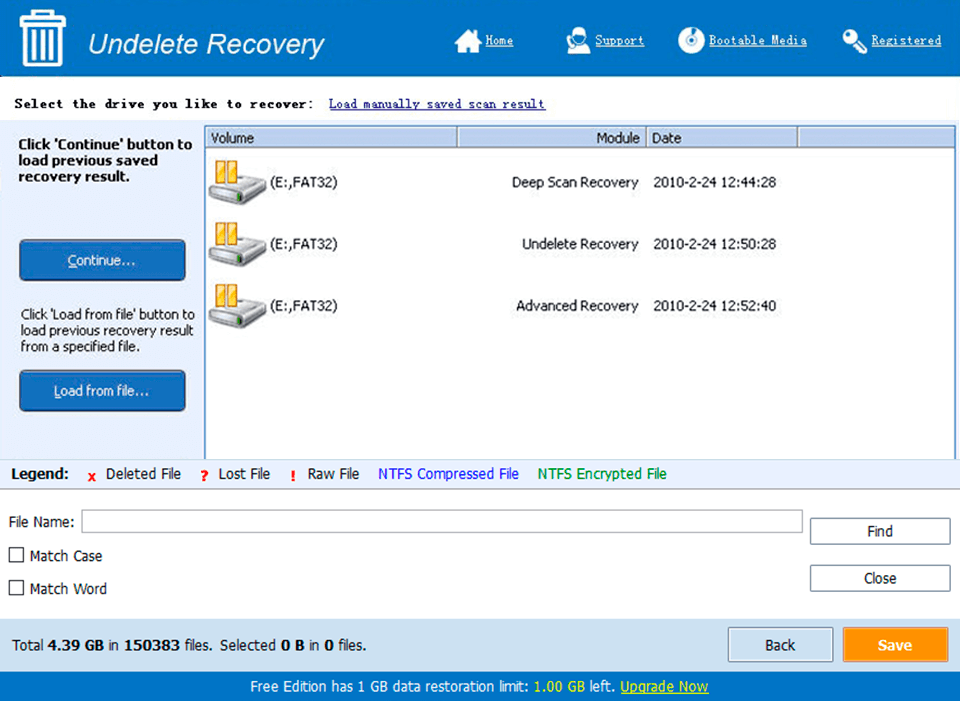

Screen Shot

System Requirements for MAD Global Thermonuclear Warfare serial key or number

- First, download the MAD Global Thermonuclear Warfare serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: